Feedback trap

strategymarketingproduct development

Bronislav Klučka, Feb 10, 2026, 12:34 AM

Bronislav Klučka, Feb 10, 2026, 12:34 AM

I probably don't need to explain to anyone that when you create a product, you need some feedback from customers, some customer research - you simply need to ask customers questions. But what if I told you that many of the answers are lies, games, politeness... And your product is built on the lies, games, and politeness of those surveyed.

In this series, we’ll move from what customers say, to what customers choose, and finally to what customers are actually trying to accomplish.

Problem

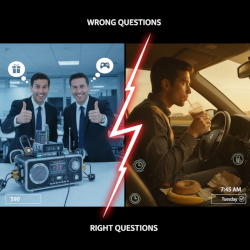

The problem here is questions/surveys conducted by product development or marketing that contain questions such as:

"Do you like our product?"

"What feature would you like to see added?"

"What don't you like about our product?"

And finally, because this metric is very popular: NPS (net promoter score - "would you recommend our product?") - NPS is a highly overrated metric, designed to make the respondent happy and say "yes." It is an indicator of your social status, not of value to existing or potential customers.

In these cases, "better no data than distorted data" applies.

The problem is what and how we ask.

Social Desirability Bias

Social desirability bias says that people choose the answer that is expected of them.

Maybe they don't want to look bad: "Would you buy this bag made from 100% recycled materials?" "Sure." After all, we want to look like we care about the environment.

Maybe they want to make you happy and avoid explanations and conflict: "Do you like our product?" "Sure." It takes courage to say "no," and then there's the threat of unpleasant questioning.

In 1985, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (authored by Icek Ajzen) was published, which was subsequently confirmed by a lot of research (e.g., a 2001 meta-analysis of 185 studies, Armitage and Conner). Among other things, TPB describes the difference between what we say and what we do. What we say is influenced by social norms, personal values, and the expectations of others. What we do is influenced by the cost of the action (how difficult it is) or the reward for the action (what we get out of it). Very simply, there can be a difference - the motivators are different. That is why the answers in the questionnaire are optimized for the social situation, while purchasing decisions are optimized for personal benefit.

Personally, I call this a "giftable" answer. The respondent wants you to feel good, or he/she wants to feel good about the answer.

Strategic Misrepresentation

Strategic misrepresentation says that people choose answers that guarantee them some kind of advantage.

"Do you want us to add this feature?" "Sure." Maybe they'll get it for free with their subscription. Do they need it? It doesn't matter, they're getting something for free. Maybe they'll get a free sample of your product, so they answer in a way that will make you happy.

We lie to get a grant. We lie to look better in front of potential partners. We lie to avoid punishment...

There are studies on this topic as well (2004 Steinel et al., 2010 Hall et al. and many others).

Personally, I call this a "gamable" answer. The respondent wants to gain something and plays the game.

Case "milkshake"

At the end of the 1990s, a world-famous fast-food chain wanted to increase sales of milkshakes. They identified a demographic group: mothers with children, and began asking what they could do to make this demographic group enjoy milkshakes. They did everything, tried everything. Sales did not increase.

Clayton Christensen, a professor at Harvard, entered the scene and immediately identified the first mistake - the target group was just an idea, unsupported by anything. So one day, they stood in front of the store for 18 hours, measuring who was buying milkshakes, and found that 40 - 50% of all milkshakes were sold before 8:30 a.m. to drivers in cars. They then asked them a completely different question: "What job did you hire this milkshake to do?" They didn't ask if they liked it, or if they would recommend it, they asked about the specific added value.

a banana is not filling enough,

a doughnut is sticky (difficult to eat while driving),

a baguette is too dry, crumbles, and the dressing drips out.

A milkshake is filling, comes in a sealed container, and can be eaten while driving. The milkshake fulfilled the role of a convenient meal.

Fast food subsequently made milkshakes thicker (more filling), optimized the purchasing process (to make it faster and more convenient), and sales increased approximately fivefold...

In this article, we have shown why most marketing surveys are just an expensive game of truth. People "give" you positive answers or strategically manipulate feature requests to get the most out of the survey for themselves. The result is the infamous "milkshake" that no one buys because it has no clearly defined purpose.

But what happens when we stop talking and start actually doing business? What happens when we force customers to make a tough choice between a "valuable" product and cash?

Imagine you have a top-of-the-line radio worth $150 in your hand. It's beautiful, has great sound, and people would give it 10 out of 10 in a survey. And then you offer people: "You can keep this radio or take $35 in cash."

Most people will take the money.

Why would anyone trade $150 for $35? Are they crazy? No. They are the most rational people in the room. They have just uncovered the Value Gap - the gap between the price tag and the actual value.

In the next episode, we'll look at research by Joel Waldfogel and Tversky & Shafir that explains why an "overpriced" product with a high price tag may have less value to the customer than a few hundred dollars in their wallet. We will reveal the truth about what economists call "Deadweight Loss" and why your efforts to add features are actually destroying the value of your business.

And finally? Finally, we will look at the basic, general "tasks" that your product can perform for the customer.

The question is not what the customer wants, how they like you, or whether they would recommend you... The question is: "What specific task does our product perform for you?"